After finishing medical school and learning exactly how and by whom a patient is seen in the hospital, sometimes I worried that I would be a human guinea pig. I was afraid that if I were to go to a teaching hospital, meaning a hospital that has residents and medical students, they would practice their “first-timers” on me. Let’s say I need a surgery. Maybe a student who has never sutured in their life gets to practice on my belly. Or if I am hospitalized with a common complaint, e.g. pneumonia, maybe a student will tell the other doctors the wrong story about me and I will receive the wrong medications. As an applicant to medical school, or a newly accepted medical student, knowing the little you do know, maybe you’ve thought these very same thoughts.

The reality is that teaching hospitals are fantastic. The attending physicians (the doctors who oversee both residents and medical students) are well-educated and always on their toes. They must be, otherwise how could they teach? With medical students around who are fresh off the books and residents who are recently trained in different fields of medicine, you’re bound to bring many more ideas to the table. This includes differential diagnoses, appropriate medications to treat the condition, potential rare drug reactions that may come from them, and many more eyes and ears on the patient as they recover.

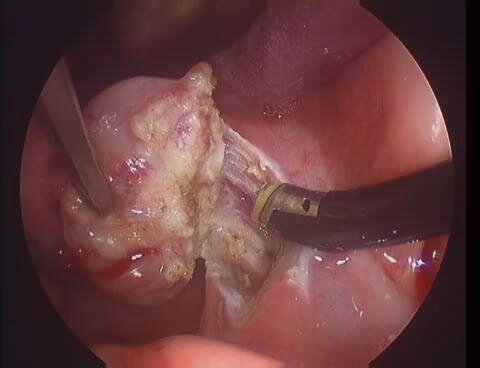

But that still takes me back to hands-on skills. Maybe you have wondered how doctors become good at techniques. How does a medical student become a surgeon without ruining beautiful skin with horrible amateur scars? My answer to you is pig feet. There are practice boards to suture on, but nothing gets as close to human skin as pig feet. Granted, the skin is tougher than most human skin (hence why they make leather out of pig skin), but the tensile strength and elasticity of the dermal and epidermal skin layers is out of this world compared to synthetic practice boards or cloth.

Although I consider myself a pescetarian, for the sake of all my patients to come, I’ll keep practicing on these little piggies.